Even electrical engineers, like Nikola Tesla, used words like "energy" to describe that which was generated by electricity and that which he felt after sleeping. It's not clear that many people distinguished between the two. Tesla actually got the idea for tuning radio frequencies through his belief that he and his mother were tuned into the same frequency when she died. Still, Tesla understood more about electricity than most people do today, but the electrical revolution was spreading rapidly.

A town called Godalming, Surrey, built the first central station to provide electricity to the public in the fall of 1881. They did so because the disagreed with the rate the gas company was charging them. I understand the feeling from dealing with my internet provider. Godalming's system was first used for their street lamps, but within the year more than 80% of its homes were connected. Overall, the town wasn't happy with their new electrical system and reverted to gas (also a familiar feeling in dealing with new internet providers). However, by 1882, London had a large-scale power station at Holburn Viaduct.

The power Holburn Viaduct produced was mostly used to power public resources. In spite of widespread apprehension the rails of the London Underground were being electrified. People worried about potentially-fatal electrical short circuits and dangerous accidents. London's Bersey Cabs hit the London streets in 1897. By 1899, ninety percent of New York City's taxi cabs were electric. Electrification of the home was reserved for the most forward-thinking members of the upper class, with the Savoy Hotel being the first such establishment to run its lights and lifts on electric power. While this impressed many of its guests, the popular imagination still viewed this new power source with as much fear as it did curiosity.

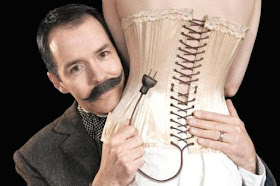

Many people believed electricity could recharge their bodies. The field of medicine was experimenting with electricity. Even rural doctors would charge for coursing low levels of electric current through the body in an effort to cure a variety of real and imaginary ailments. Of course, wherever you could find a quack Victorian doctor, you could find quack Victorian products.

I don't know what electric oil was, but it sounds like wonderful stuff. Moreover, I'm also not sure how you get electricity in a bottle.

In the midst of all this electric healing, electricity was deliberately used to kill for the first time in 1890, when a convicted murderer, William Kemmler sat in the electric chair on 6 August 1890. The first attempt left Kemmler unconsciousness, but did not stop his heart and breathing. After they recharged the generator, the second attempt ruptured blood vessels under Kemmler's skin; the areas around the electrodes singed. Kemmler's execution took about eight minutes. George Westinghouse later commented that "they would have done better using an axe," and a witnessing reporter wrote that it was "an awful spectacle, far worse than hanging." Some say Kemmler burst into flame before finally dying.

Thomas Edison horrifically played on the public's fears about the dangers of electricity when attempting to discredit his competitors by electrocuting and torturing dogs, cats, cows, horses, and most famously, an elephant in public demonstrations.

In conclusion, 1890s people thought electricity had the potential to replace gas as a fuel source; that it was deadly dangerous; but that in small amounts, electricity had magical healing powers. I've read just enough to believe the rumours that some people actually wore electric jewelry for its healing powers and will leave you with the steampunk Jem image that conjured in my mind. The reference here is, of course, to Jem's flashing earrings.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!

If you have enjoyed the work that I do, please support my Victorian Dictionary Project!

In conclusion, 1890s people thought electricity had the potential to replace gas as a fuel source; that it was deadly dangerous; but that in small amounts, electricity had magical healing powers. I've read just enough to believe the rumours that some people actually wore electric jewelry for its healing powers and will leave you with the steampunk Jem image that conjured in my mind. The reference here is, of course, to Jem's flashing earrings.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!

If you have enjoyed the work that I do, please support my Victorian Dictionary Project!