|

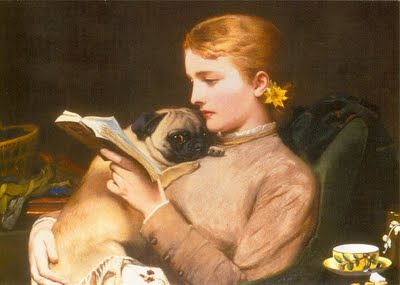

| "Blonde and Brunette" by Charles Burton Barber |

Soon after Brassey made them cool, Queen Victoria became fond of the breed. She had several and it was through her involvement in breeding pugs that the Kennel Club was established in 1873. It was, consequently, a pug who won the first best in show of the Westminster Kennel Club in 1877.

Dog fancying is linked to the Victorian cult of domesticity, supported by the Queen, who commissioned a painter, specifically Charles Burton Barber, to capture her beautiful dogs (and others) on canvas.

|

| "A Monster" by Charles Burton Barber |

I've been wearing mostly jeans, and one blazer has already had a few threads pulled since I got my own little brindle pug a few weeks ago, so I am astonished at that dress. All of the pictures above depict scenes of feminine domestic bliss in the typical Victorian fashion: women and children in household settings with their pets. But, as with everything in the nineteenth century, nothing was as simple as it seemed.

Before Victorian England embraced them, pugs were part of a very masculine culture in continental Europe and this is where it gets really weird.

The Mops-Orden (German for the "Order of the Pug" was a Catholic para-Masonic society that was supposedly founded by Klemens August of Bavaria in 1740 to bypass a papal bull. To the Order of the Pug, the pug represented loyalty, trustworthiness and steadiness, whereas now they are known primarily for their flat faces and love of cheese. Those who belonged to the Order of the Pug were called Mops (Pugs). New members underwent an initiation process that involved wearing a dog collar and behaving, in various ways, like a dog: scratching at the door to get in and kissing a porcelain pug's bum.

The secrets of the Order of the Pug were exposed in Amsterdam in 1745, but it took three years for anyone to ban them (maybe it took that long for them to take it seriously). However, it is rumoured that the Order was active until 1902.

|

| A Pug by Carl Reichert (1836-1918) |

Aside from Queen Victoria's pugs, Minka, Venus, Rooney, Olga, Fatima and Pedro, the most famous pug in European history is probably a little guy, called "Pompey," who, contrary to Monty Python lore, expected the Spanish Inquisition and alerted his master the Prince of Orange William the Silent to their arrival in 1572, thereby saving his life.

So while it is popular to trace the pug cult back to Queen Victoria and Lady Brassey, it has most certainly been around a lot longer than that!

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!So while it is popular to trace the pug cult back to Queen Victoria and Lady Brassey, it has most certainly been around a lot longer than that!

|

| Queen Victoria and one of her pugs. |

If you have enjoyed the work that I do, please support my Victorian Dictionary Project!