"It is merely a question of head," said Percy Anderson to me one day, whilst we were discussing some easy method of solving a problem of fancy dress.Thus begins Mrs Aria and Percy Anderson’s Costume: Fanciful, Historical, and Theatrical (1906). Who better to speak on the subject of costume than the gossip columnist and editor of the World of Dress, Mrs Aria, a.k.a. Eliza Davis.

And he continued:

"Indeed, I would say that, broadly speaking, of all costume. The fashion of any period is distinguished primarily by the way its wearer dresses her hair.

"And chooses her sleeves," I suggested, and received his approval.

Because clothes are so fascinating, I’ve gone off on this wonderful tangent into late-Victorian fashion magazines, but I actually came across Davis through a more solemn matter. Over the weekend, a friend complained that Oscar Wilde was anti-Semitic. I’ve encountered mutterings about his terrible attitudes before and do not intend to diminish any of them, but thought I would look for his anti-Semitism. What I found was an anti-Semitic passage in The Picture of Dorian Gray, which certainly makes Dorian seem like a bit of a jerk (but he’s supposed to be. That’s the point of how he lives his life.) but it doesn’t say much about Wilde’s own views. Secondary sources defend Wilde by becoming as horrid and cliche as possible: “But... but... but, Wilde had Jewish friends!” Then, I found Davis.

Davis writes a little about Wilde and his brother in her autobiography, My Sentimental Self (1922).

Both Oscar Wilde and Willie Wilde became frequent visitors, and in a public garden which spread its ill-kept lumpish lawn behind our dwelling we often played tennis together : Willie in a shirt showing some desire to be divorced from the top of his trousers, and Oscar in a high hat with his frock-coat tails flying and his long hair waving in the breeze.Because Willie is the real focus of my research (not that you can tell by reading my blog), I forgot all about his younger brother and started looking into the life of his fashionable, ambitious, and gossipy friend.

Davis was Julia Frankau and Owen Hall’s sister, making the Davises a very writerly family. Her niece would later recall that Davis knew loads of literary icons and collected their autographs for her and her own siblings. Really, I think, Davis was poised for success as a gossip columnist.

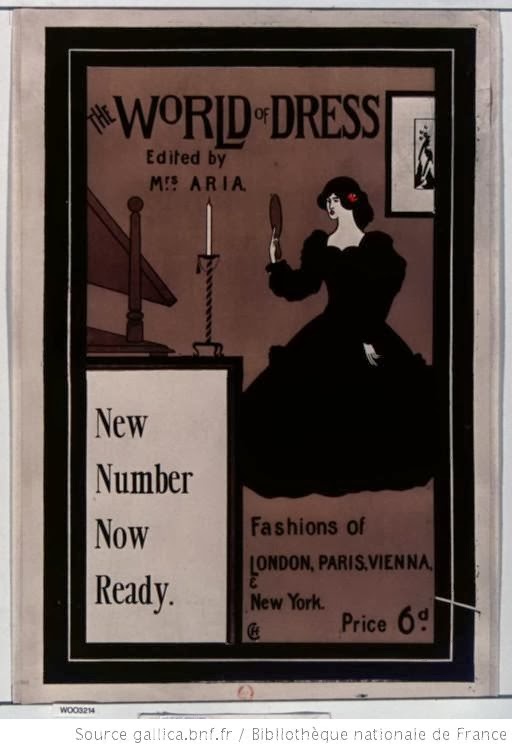

Whilst I was working for Hearth and Home I conceived the notion that I must possess and edit a journal of my own. Thus came into existence the monthly magazine known as The World of Dress, destined of course to show all other editors how fashion papers should be conducted.

Other than Davis’s own opinions of it, I’m unable to find much information on the World of Dress. As is the case with most woman writers of the period, more is written about her love affairs than her work. On the other hand, gossip is gossip and gossip was Davis’s business.

Margaret D. Stetz wrote a lovely short essay on the relationship between Wilde and the Davises. In an effort to return to what led me along this tangent in my research, I conclude with her thoughts:

The World of Dress possessed many excellent features from many excellent sources. Fashion news from Paris, Vienna and New York, interviews about dress with famous people. Sir James Linton, Sydney Grundy, Max Pemberton, Mortimer Menpes, Downey, the royal photographer, and lastly and most amusingly Dan Leno gave opinions. Casually Dan Leno declared that he of all men best understood women's clothes because he had worn them for years; and he knew all about them from the inside; the property to secure more laughter for him than anything else in his mirthful career being an old wired bonnet, tapped on and tied with strings. Every time it came off he just tapped it on a different part of his head, and the audience roared.As illustrated throughout her autobiography and her work on dress, Davis had a healthy sense of humour. Biographers have noted that she and her sister didn’t take shots at Wilde after his tragedy in 1895, but even defended him against the homophobia of their brother.

Margaret D. Stetz wrote a lovely short essay on the relationship between Wilde and the Davises. In an effort to return to what led me along this tangent in my research, I conclude with her thoughts:

In The Picture of Dorian Gray and elsewhere, Wilde produced caricatured portraits of Jews. But in later years, his Jewish literary contemporaries also drew portraits of him, sometimes favorable and sometimes not. What all these differing representations signify about the ‘true’ social attitudes and personal views of those who populated the cosmopolitan artistic circles of late-Victorian London remains a mystery even deeper than the question of why Basil Hallward’s painting of Dorian aged and changed.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!

No comments:

Post a Comment