Eight posts ago, I started a series on 1890s male sexuality, and expected to wind up characterizing the 1890s gentleman and his sexy self as Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, but the novel itself can be read as a critique of societal expectations of male sexuality.

The strange sense of man's double being which must at times come in upon and overwhelm the mind of every thinking creature gives us the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and its posing and eliding of the issue of man, sliding as it does between male and human, between a sexual-instinctual problematic of masculinity and an undifferentiating psychological recognition of the beyond of consciousness, of ego and id. The story starts from the exclusion of the woman which is the condition of a questioning of the man and also its limitation, the specifics of difference are pulled back into general themes. The title, in fact, is misleading or, to put it another way, is itself one of the precautions and a symptom of the problem of representation: nothing about the story is really strange other than that it should be thought strange, the strange case of male sexuality is precisely unstrange by being made into this strange case which comes out of, works with the assumptions of, the given system of representation. Male sexuality is neither the foregone conclusion of animal passion nor the horror of an unspeakable darkness but once it is envisaged within this system that is all that can be said, all that is allowed.

I love-love-love this passage in

Stephen Heath's "Psychopathia sexualis: Stevenson's Strange Case." I love the essay for what it is, and love this passage for how it speaks to this series of posts. For over a month now, I've been talking about male sexuality as if there is some difference between male sexuality and human sexuality, and I've been trying to limit the discussion of female sexuality. Picturing sexuality as animal passion, is it wrong to assume that there was any difference in sexuality 120 years ago? Surely, as animals we can't have changed that much.

|

| Eugen Sandow |

I began this series by discussing

1890s male body image. The ideal male form was characterized as much by ability as it was by form. Form, they had discovered, could be sculpted, and doctors were already refusing to treat obese patients.

In my discussion on sexual orientation, I showed you how they were inventing the modern concept of homosexuality. Men having sex with other men wasn't new, but the act of letting the action define who one was was new. Identities carry power. As a heterosexist society, 1890s London mobilized to limit the power of homosexual identities by outlawing it, and redefining it as a form of mental illness. In spite of the homophobia that this gave rise to, I think that homosexual men in the 1890s were better off than the men who had no labels because they must have felt less alone.

Which brings me to

my post on masturbation: everybody did it, but Victorians worked very hard to make each other feel bad about it. The rumors about what masturbation could do to your health were almost as bad as the remedies for masturbators. It was during this post that I felt the most like I would end up with a Jekyll and Hyde conclusion because it seemed that people feared sex so much that the most reasonable personal solution was to keep it a secret.

Thankfully, that's not generally what they were doing. Homosexuality wasn't the only new identity an 1890s guy could wear. People were trying out aestheticism, being a Bohemian, they were even switching religions, and

inventing new religions. In many ways, the 1890s were like the 1960s, but people dressed better. It seems that they were even beginning to understand that the identity of 'man' or 'woman' is one that we create for ourselves, but the full realization of that notion still seems a long way off.

There were both male and female prostitutes, just like there have always been, but the motivation of male prostitutes was perceived differently from the motivation of female prostitutes, much the same way the idea of being a male porn star today is quite different from the idea of being a female porn star.

My discussion on prostitution made it clearer to me that the main difference between 1890s male sexuality and 1890s female sexuality was the concept of agency.

Men were perceived as having these out-of-control sex drives, whereas women weren't supposed to have a sex drive at all.

What little sex education existed in the 1890s existed exclusively for young men. On the other hand, all responsibility for the transmission of STDs fell on the heads of female prostitutes.

In many ways the increase in religious and spiritual feeling at the end of the 19th century can be linked to the Darwinian Revolution and the need some people felt to differentiate themselves from animals. Sex was viewed as a baser instinct, an act they had in common with every other mammal on the planet. Morality was used to condemn anything they didn't like, and science was frequently used to back those notions up.

Disease could then be read as a moral failing, linked to the degeneration (rather than upward evolution) of mankind.

I couldn't talk about 1890s male sexuality without talking about women. Women were cast into a separate sphere, dressed up as a morally-outstanding potential wife/mother, taught to refuse all sexual advances, and portrayed as the antidote to all male sexual problems.

If

Eugen Sandow was the perfect man, the perfect woman knew nothing about sex and was a virgin until the horrible night that she got married. Her life's ambition was to become a mother. The perfect woman had no aspirations outside of keeping a perfect house to raise her perfect children in. She would refuse sex to her husband whenever he asked for it, and would refuse to take her clothes off when they did it.

If you were a man and were less than perfect in any way, common sense of the day suggested you find that woman and

marry her straight away because she would cure your masturbating, she would reduce your sex drive, and she would shape you into the kind of man who could carry a family of six on his shoulders.

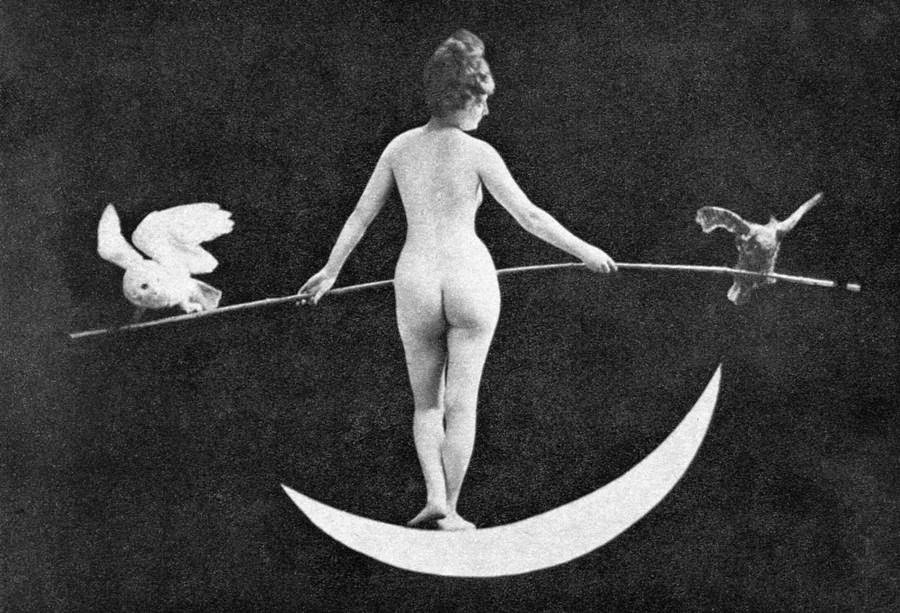

Basically, women were needed to balance out the baser instincts of male sexuality and to harness his ambitious nature, while directing him along the right path in life. That path steered clear away from

pornography, masturbation, and dirty pictures, and on toward a bland diet, lots of exercise, and kids to ignore. The kids were her responsibility.

We know, of course, from the biographies of nearly every writer ever mentioned in this blog that, even if this was the ideal, it was almost never the reality, and more married couples lived apart in England and Wales than in any other part of Europe. Like Jekyll and Hyde, there were probably some men who lived double lives, just as there are today, but for the most part, people couldn't help being whoever they were, even if society was working really hard to make them feel bad about it.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook

page for updates!

If you have enjoyed the work that I do, please consider supporting

my Victorian Dictionary Project!