|

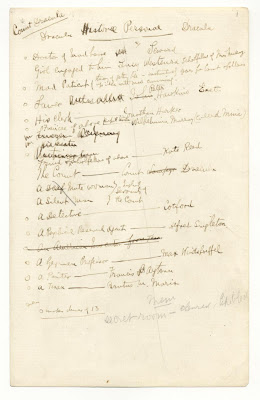

| "The Hooligans," by Leonard Raven-Hill (1899) |

A cold rain began to fall, and the blurred street-lamps looked ghastly in the dripping mist. The public-houses were just closing, and dim men and women were clustering in broken groups round their doors. From some of the bars came the sound of horrible laughter. In others, drunkards brawled and screamed.The first five words tell us this isn't going to be a pleasant night. The rain is cold and it is just beginning. This rain isn't cleansing, but a "dripping mist," like the fog of London -- only wetter.

We know it is dark because the street lamps are on, but rather than lighting the way the street lamps are "blurred" and "ghastly." Ghastly things cause terror. How can a street lamp be ghastly? A ghastly street lamp causes terror by exposing it. Light makes the dark more frightening by providing glimpses of what is hiding in the dark.

|

| Source. |

The public houses, referred to in the second sentence, were East End pubs and taverns. It's closing time. The drinks of last call are done. The "dim men and women" are drunk. Of all the Victorian words for drunkenness, Wilde chose "dim" for the continued allusion to light. The men and women are dim in the ghastly light of the street lamps.

We may also assume that these were ghastly men and women. Respectable Victorian women didn't drink in public houses, or in public at all. The fact that they do here is part of the depravity Wilde wants to portray. Drunken women mingling, or "clustering in broken groups," with drunken men implies loose morals and possible prostitution. Poverty and drunkenness were Victorian character flaws caused by loose morals. Women could not easily be forgiven for ever having demonstrated such character flaws; Lady Meux was shunned by respectable society her entire life because she once worked in a public house.

"From some of the bars came the sound of horrible laughter." The perceived depravity of the poor and drinking classes makes their laughter horrible. In the public houses where they aren't laughing, they are brawling and screaming. Before Dorian even steps out of his carriage, this is the scene that readers see him in.

|

| Source. |

I will read the next paragraph in my next blog post. In the mean time, you can read The Picture of Dorian Gray at Project Gutenberg. For more information on 1890s slums and slumming visit the Victorian Web.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!