Marriage

“A man who moralizes is a hypocrite, and a woman who does so is invariably plain.” - Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere's Fan.Victorians generally viewed heterosexual marriage as beneficial to both men and women. Marriage and motherhood were the ultimate goal for a young woman. In the separate spheres ideology, women were portrayed as the angel of the household and a wife would act as her husband's moral compass. In this view, corrupt men could be reformed by such a woman.

Even today, the heterosexist binary view of gender paints men with sex drives that they will not be able to control if women aren't chaste enough. Ideally, the Victorian wife's refusal of sex tempered her husband's raging libido. Of course, we know none of this is true. Men do not necessarily have higher sex drives than women, and many people would give anything to turn their marriages into "an orgy of sexual lust." But, in the Victorian era, if you were a man, who masturbated or thought about having sex with men, marriage to a woman, who would ideally refuse to have sex with you, would somehow save your life.

History is full of examples of this not working out very well. Oscar Wilde is one example, though friends speculated, at the time, that, perhaps, he had married the wrong woman, and that if he had married his first love (Bram Stoker's wife), none of his same-sex relationships would have ever taken place.

Florence Stoker is an example of the ideal Victorian wife. The Stokers had one child. After he was born, his parents stopped having sex. Although there's evidence that Bram Stoker may have had many homosexual fantasies, there's no evidence that he ever cheated on his wife, even though they spent most of their time apart (he was busy working and travelling).

Although I don't think that Oscar marrying Florence would have prevented his affairs, I don't think that either of them were happy in their marriages, even though Florence was such a 'good' wife. They pined for each other, and neither were completely happy with their spouse. So, what happened when someone was unhappy with their spouse in the 1890s?

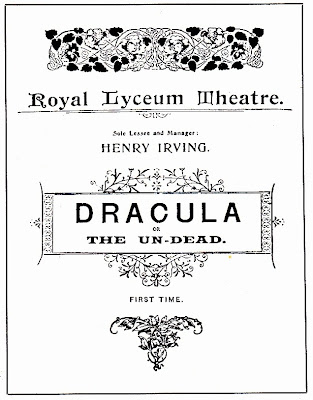

Bram Stoker's employer, Henry Irving got married in July 1869. One night in November 1871, when she was pregnant with their second child, his wife criticized his work: "Are you going on making a fool of yourself like this all your life?" They were riding in a carriage, and Irving stepped out of it at Hyde Park Corner. Their paths would never cross again. They never divorced, and when Irving was knighted for his work, his wife styled herself "Lady Irving."

Irving's case was not exceptional. Contrary to popular belief, marriage was very unstable in Victorian times. Private separation deeds were common place and not confined to the upper-classes, as poor and working class people also sought to avoid the embarrassing scandal of divorce.

Martha Tabram, possibly the first victim of Jack the Ripper, had parents who separated, then had a troubled marriage herself, due to her alcoholism. Her husband left her in 1875, and paid her 12 shillings a week for three years. He reduced this amount to two shillings and sixpence when she moved in with another man.

Further contradicting popular beliefs about Victorian marriages, many couples of all classes lived together without ever getting married. Oscar Wilde's brother lived with his second wife for about a year before they were married. In the Murder of Mrs and Baby Hogg, we learned that the killer lived with a man before moving in with Mr Hogg, and had assumed that first man's name without marrying him.

With real life providing so many examples that contradicted the mainstream ideal of what marriage should be, writers and readers in the 1890s questioned the institution of marriage on legal grounds, and based on human desire. With the support of women writers mentioned elsewhere in this blog, legal reforms began to support women's property rights in marriage, and after it. As the Darwinian Revolution began to scientize the way people thought about themselves and their basic instincts, people questioned the monogamy that traditional marriage demanded. If men supposedly had such strong libidos, maybe they weren't meant to be with just one woman their entire lives.

The marriage question, also sometimes referred to as 'the sexual problem,' brought with it the concept of 'varietism.' According to Anne Humphreys, 'varietism' meant anything from promiscuity to serial monogamy, and the language used to discuss it was cloaked in evolutionary theory. This need to describe sexuality in terms of evolutionary theory ties back into people's needs to justify desires that were not condoned by their religious beliefs.

Although they thought and wrote about it an awful lot, the marriage question was never really answered in the 1890s. Though they thought about 'varietism' and engaged in alternatives to conventional married life, none of it was ever fully embraced by the more dominant aspects of their heterosexist culture. In 1912, Dr Muller-Lyer wrote:

The body of available and necessary knowledge to be taught the young became larger, the task of imparting it more difficult, and it was essential that family life should become consolidated, for much of this instruction could only be imparted by and in the family. And therefore monogamy became more frequent and met with definite approval, and unrestrained varietism in sex relations began to appear harmful, exceptional, and disreputable.Consequently, the marriage question was thought about and written about throughout the twentieth century, and the way that we discuss it reflects the challenges of our times. Like most nineteenth and early-twentieth century German texts on evolutionary theory, eugenics, and race, Muller-Lyer's book is loaded with racism and classism, but he does suggest that we stop morally judging our ancestors for their sexuality, which is an attitude that should be applied to the way that we think of our contemporaries as well.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!

If you have enjoyed the work that I do, please consider supporting my Victorian Dictionary Project!

_188_unknown_photographer.jpg)

.jpg)

NjQbBP(rN9LTDg~~60_35.JPG)

.jpeg)