|

| Walter Lambert's ‘Popularity’ - A vast painting depicting the Music Hall Stars of the early 1900s |

When a Mail representative found a respectable looking, rather portly gentleman with an eyeglass, a frock coat, a tall hat, and a walking stick, occupied in the dingy daylight of a mid-day rehearsal, and tra-la-la-ing a tune over to the leader of the orchestra, the figure turned out to be no other than that of the composer of a hundred comic songs which have been whistled, sung, played on barrel organs, yelled at free-and-easies, and otherwise tuned to the world. - The Era (July 1890)

|

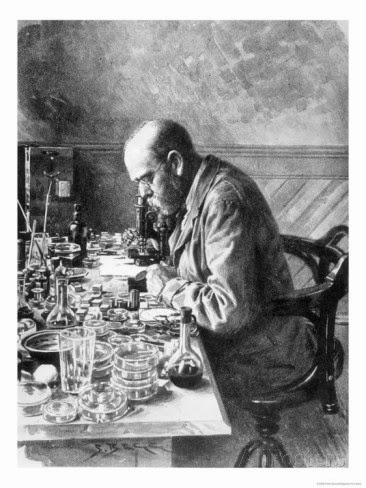

Arthur Lloyd, as depicted

by Walter Lambert |

That portly gentleman is none other than Arthur Lloyd, a Scottish-born music hall singer, songwriter, comedian and stage producer. The first major star of London's music hall scene, Lloyd wrote more than 185 songs, all of which have since been forgotten, except "Married to a Mermaid," which, I must confess, I never heard of before. He was even, on occasion, called to do command performances for the Queen.

In the Era, Lloyd professes that his father was a comedian. Before his own career in musical comedy got under way, Lloyd made money selling his songs directly to the publishers, and it was as if the trend of the late-19th century was tailored for him. Music halls were constructed, like great palaces, all over the city, but especially where land was cheaper in the East End.

In doing so, the music hall took institutionalized music out of the hands of the wealthy and created commercial music for the masses, helped along by the Copyright Act of 1842, which protected the reproduction and performance of music and created economic stimulus for writers, performers, and publishers. In the years that followed, the tavern concert room increased in size, until these purpose-built halls arose.

Arthur Lloyd performed in music halls all over London.

A full program from the Royal Trocadero Music Hall, dated 24 June 1890 in available online, and includes other acts of the evening, including: a troupe of acrobats!

Lloyd's music to have appealed to the general public. Titles include: "The Postman," "Three Acres and Cow," "The Brewer's Daughter," "Ill Used Organ Man,""Mounseer Frenchy," and

many more!

I will leave you with the lyrics to "Drink And Let's Have Another" (1891).

Drink And Let's Have Another

Billy Tomkins, McNab with Montgomery and Brown,

And myself t'other night at our club all sat down;

And every one swore he would spend his last "brown"

In treating his pals all around.

And after we'd had a few drinks in the place,

Billy Tomkins arose with his jolly red face,

And said, "I will not be outdone in the race,

For I shall stand glasses round!"

Chorus:

Drink up boys and let us have another,

That last round's made me feel fine;

Drink up boys and all your troubles smother,

You've stood your round and I'll stand mine!

We drank that round quickly to keep out the cold,

And a precious good story Montgomery told;

But e'er we broke up poor Montgomery rolled,

And helplessly lay on the ground.

Then Brown, undertaker ,who ne'er makes a noise,

But in miserable fashion his liquor enjoys,

Said, "Now then I hope you'll allow me my boys,

This time to stand glasses round!"

Chorus:

I told you Montgomery was down on the floor,

But whenever he heard orders given for more,

Said he'd have another, which made us all roar,

As he struggled and rose from the ground.

And when he'd drank that, he said, "Now it's my shout!"

We laughed but he said, "I know what I'm about!"

Though to-morrow I'll have a good fit of the gout,

We will have another round!

Chorus:

Although every one there was more or less boozed,

When I looked at McNab I was vastly amused,

To see that he wasn't the least bit confused,

Though he'd had fifteen drinks I'll be bound.

He scouted me when I suggested that then

We should go home to bed like respectable men,

And said we maun hae doch and doris ye ken,

And this will be the last round!

Chorus: Drink up chaps and let us hae anither ,

That last round's made me feel fine;

Drink up chaps and a yer troubles smother,

You've stood your round and I'll stand mine!

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook

page for updates!